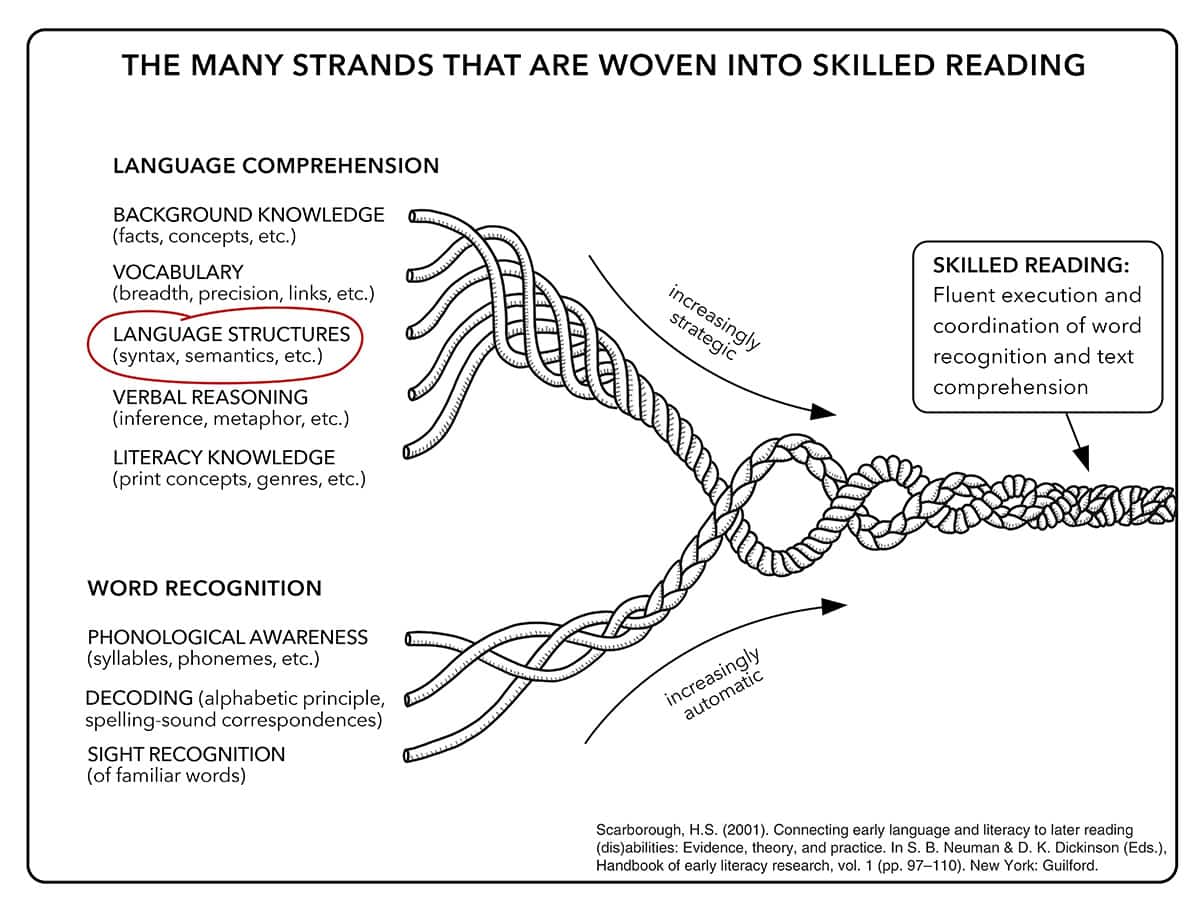

Advances in educational psychology, linguistics, cognitive science, and neuroscience have deepened our understanding of the cognitive processes involved in reading and the best approaches for instruction. Yet little attention has been given to an important consideration (using Scarborough’s versatile reading rope framework) that regardless of a child’s variety of English, the texts children have to learn to read, or “language at the speed of sight” (Seidenberg, 2018), are for the most part written in a dialect different than their own. Specifically, texts are written in the upper Midwest dialect (one of many General American English dialects) that is standardized in the published U.S. English writing system. This standardized English appears not only in academic, non-fiction texts but in many genres of literature, including children’s books.

Children who speak African American English, Latino English, and other Creole-like varieties face challenges in learning to read standardized written English (Gatlin & Wanzek, 2015). Very few educators know anything about this phenomenon, and even fewer are aware of instructional modifications that might support bidialectal students. Empirically, the research investigating effective instructional approaches is limited. During the 1990s and following decade researchers studied the relationship between dialect shifting and reading outcomes, determining that metalinguistic awareness and perhaps executive functioning are important influences on reading acquisition for bidialectal speakers (Craig, Kolenic & Hensel, 2014; Terry, 2014).

This research led to the development of a handful of commercially unsuccessful published supplemental programs intended to help teachers support bidialectal speakers in reading and writing. For example, Bridge: A Cross-Culture Reading Program (Simpkins, 1997), the program involved in the Ebonics controversy (Marshall & Hobbs, 2019), was followed by contrastive analysis-based supplemental resources (see Gatlin-Nash et al., 2020 for a summary). The contrastive analysis programs were designed for students ranging from pre-K through high school (i.e., Edwards & Rosin, 2016; Maher, Mazzei et al., 2024; Terry, Connor & Thomas-Tate, 2017; Byrd & Brown, 2021; Wheeler & Swords, 2015). Much of the resistance to these programs was likely due to varying worldviews regarding the linguistic descriptors the authors used (Maher, Blomquist et al., 2024). Current research on bidialectal instruction involves translanguaging, a pedagogical approach developed for bilingual learners (Mena, 2019; Privette & Saechao, 2024). Despite continued scholarship on this topic, a lack of culturally-linguistically responsive instructional methods for literacy acquisition continues to be a barrier to school success for many bidialectal learners (Terry, Gatlin & Johnson, 2018).

References

Byrd, A., & Brown, J. A. (2021). An interprofessional approach to dialect-shifting instruction for early elementary school students. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(1), 139–148.

Craig, H. K., Kolenic, G. E., & Hensel, S. L. (2014). African American English speaking students: A longitudinal examination of style shifting from kindergarten through second grade. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 143–157.

Gatlin, B., & Wanzek, J. (2015). Relations among children’s use of dialect and literacy skills: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(4), 1306-1318.

Gatlin-Nash, B., Johnson, L., & Lee-James, R. (2020). Linguistic differences and learning to read for nonmainstream dialect speakers. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 46(3), 28–35.

Edwards, J. R., & Rosin, P. (2016). A prekindergarten curriculum supplement for enhancing Mainstream American English knowledge in nonmainstream American English speakers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 47(2), 113–122.

Maher, Z., Blomquist, C., Byrd, A., Oppenheimer, K., Shockley, E. T., Thonesavanh, T., … & Edwards, J. (2024). Does a dialect-shifting curriculum help early readers who speak African American English? Results from a randomized controlled study. Reading and Writing, 1-21.

Maher, Z., Mazzei, C., Terrell Shockley, E., Tonesavahn, T., & Edwards, J. (2024). Multiple approaches to ‘Appropriateness’: A mixed-methods study of elementary teachers’ dispositions toward African American Language as they teach a Dialect-Shifting Curriculum. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(3), 468–486.

Mena, M. (2019, October 31). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. [YouTube video]. The Social Life of Language.

Privette, C., & Saechao, K. R. (2025). Black languaging IS translanguaging: We not just talkin bout it, we bout it bout it!. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 10(1), 64-73.

Seidenberg, M. (2018). Language at the speed of sight: How we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it. Basic Books.

Simpkins, G., Holt, G., & Simpkins, C. (1977). Bridge: A cross-culture reading program. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Terry, N. P. (2014). Dialect variation and phonological knowledge: Phonological representations and metalinguistic awareness among beginning readers who speak nonmainstream American English. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35, 155–176.

Terry, N. P., Connor, C. M. D., & Thomas-Tate, S. (2017). The effects of dialect awareness instruction on non-mainstream American English speakers. Reading and Writing, 30(9), 2009–2038.

Terry, N. P., Gatlin, B., & Johnson, L. (2018). Same or different: How bilingual readers can help us understand bidialectal readers. Topics in Language Disorders, 38(1), 50–65.

Wheeler, R., & Swords, R. (2015). Code-switching lessons: Grammar strategies for linguistically diverse writers. Ventris Learning.